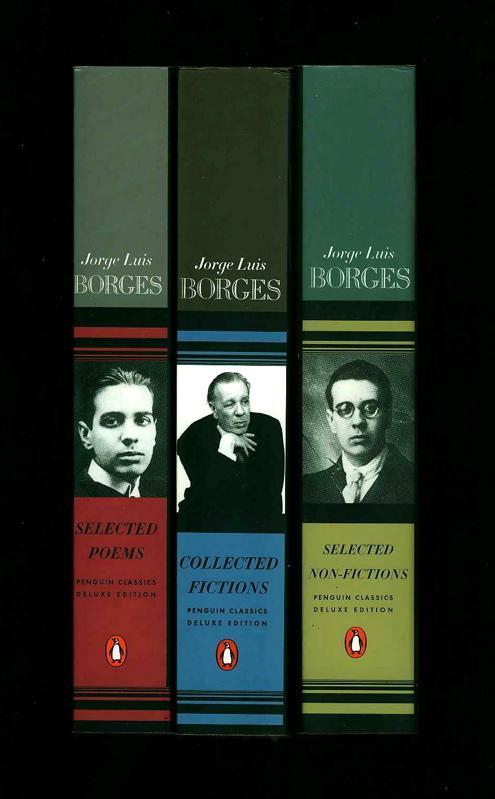

Borges’ English grandmother read him English literary classics.

His father, from whom Borges inherited an eye condition that left him blind by the age of 55, was “a marginally successful literary hand – a few poems, a so-so historical novel, and the first translation of FitzGerald's Rubaiyat into Spanish,” says Donald A Yates, one of Borges’ first American translators. He was, from the beginning, a writer attuned to the classical traditions and epics of many cultures.

The award spurred English translations of Ficciones and Labyrinths and brought Borges widespread fame and respect. He shared the prize with Samuel Beckett (the other authors on the shortlist were Alejo Carpentier, Max Frisch and Henry Miller). In 1961, he was catapulted onto the world stage when international publishers awarded him the first Formentor Prize for outstanding literary achievement. Half a century ago, when Borges’ ground-breaking collection Ficciones was first published in English translation, he was virtually unknown outside literary circles in Buenos Aires, where he was born in 1899, and Paris, where his work was translated in the 1950s. "Had the concept of software been available to me,” writes Gibson in his introduction to Borges’ short story collection Labyrinths, “I imagine I would have felt as though I were installing something that exponentially increased what one day would be called bandwidth.” He presents the most fantastic of scenes in simple terms, seducing us into the forking pathway of his seemingly infinite imagination.Ĭyber-author William Gibson describes the sensation of first reading Borges’ Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, which revolves around an encyclopedia entry on a country that appears not to exist. Borges’ use of labyrinths, mirrors, chess games and detective stories creates a complex intellectual landscape, yet his language is clear, with ironic undertones. They are brief, often with abrupt beginnings. They are fictions filled with private jokes and esoterica, historiography and sardonic footnotes. His friend and sometime collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares called his writings “halfway houses between an essay and a story”. Reading the work of Jorge Luis Borges for the first time is like discovering a new letter in the alphabet, or a new note in the musical scale.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)